Bloqs is a Social Game designed to facilitate and rekindle relationships between incarcerated fathers and their children on the outside.

Bloqs was the outcome of a six month project by a small team of four, including myself, operating within the Design Against Crime Research Centre, at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London.

The team included Alexis Bardini, Alexandra Evans, Xiangie Li, and myself.

During this time, we conducted extensive research and iterated over a range of potential design directions. We attended a conference run by South Denmark University’s Social Games Against Crime team who were responsible for Captivated, the social game Bloqs is base on. We ran numerous workshops and interviews within Prisons, with social care groups and with individuals.

Bloqs Game

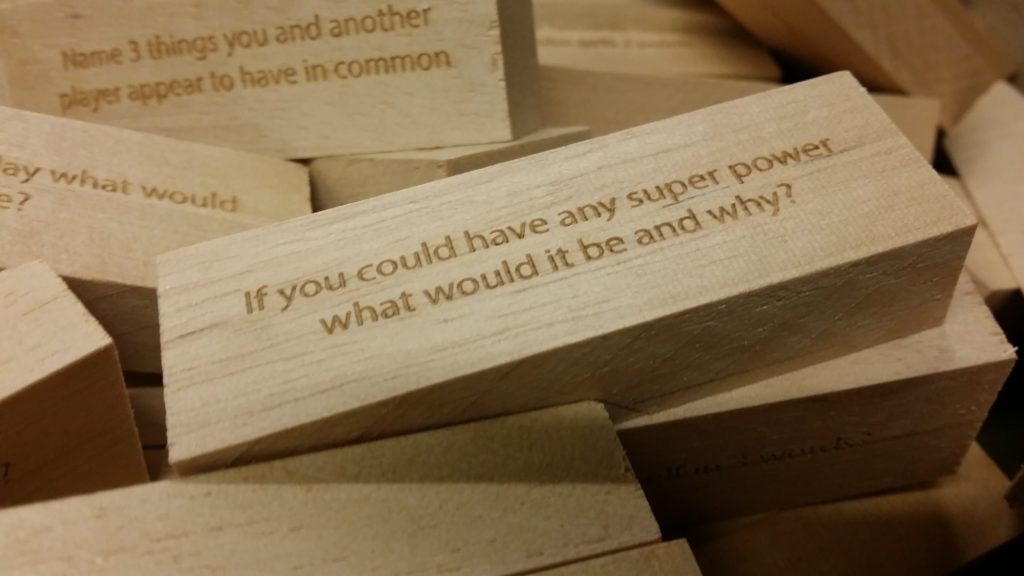

Bloqs is a Jenga-like tower stacking game where each piece, called a ‘Bloq’ has two questions or prompts written on each main face and a colour which indicates the ‘level’ the prompt corresponds to.

The players successively take a Bloq from the stack, choose a prompt which will ask them to perform an action or answer a question, sometimes involving other players. If the response is deemed acceptable by the others, the player must place the Bloq back on top and receive their corresponding money.

‘Levels’ refers to the Social Penetration theory, or onion theory, a theory of interpersonal communication and relationship that seeks to describe how relationships move from weak and relatively shallow, to deeper and more intimate connections. The colours correlate to where on the SPT the prompt aims to stimulate interaction:

- (Red) Likes and Dislikes

- (Orange) Goals and Aspirations

- (Green) Religious and Spiritual Convictions

- (Blue) Deep Fears and Fantasies

- (Purple) The Concept of the Self

The game involves a currency called ‘Squids’, based off the British slang for pound sterling, or ‘Quids’. On successful response to a prompt the player is rewarded with Squids, higher levels rewarding more.

This works to play off the inherent tension between two people who are not close by balancing that tension off of game play.

The player is incentivised to move down the ‘layers of the onion’ (take progressively higher level Bloqs) by the financial incentive which plays off against the inherent resistance to answering more difficult / vulnerable questions / prompts.

This balancing which the players will engage in is completely neutral, that is to say, a genuine trade off is made between comfort and desire to win. No coercion or forced progression though the levels is employed.

In addition, the game play format revolving around a progressively more unstable tower creates a physical tension and focuses the players attention. Even if their attention wonders during the game, the moments of interacting with the tower magnetically draw players to a single focus point. After which, the tension is eased and the players balloon back out again.

This was one of the biggest yet subtle challenges our team faced when deciding on the format of the game, as we realised through previous iterations, the risk of forced progression and vulnerability.

The game ends when the tower falls, with the last person to interact loosing 50% of their currency. The winners or looser are then determined by how much money they have, although the game is not about who wins.

The game is built on the archetype most commonly recognised as Jenga in order to utilise preexisting associations with the game and avoid having to make players familiarise themselves with an entirely new game format.

Context

It is not a particularly radical notion that Prison as a system is ineffective as a means to rehabilitate.

This is especially true in systems such as the UK justice system which relies heavily on punitive action, both during and after sentence, and has a rapidly increasing population.

When opportunities are missing and rehabilitation is not an option, incarceration can feed into a vicious cycle of crime, anti-social behaviour and derivation.

A component of this is the role of relationships between incarcerated fathers and their children. Children and adolescents with stronger connections to their parents are far less likely to suffer health issues, do well in school and avoid crime cycles than those who’s relationship breaks down.

In their younger years, kids will be brought to visit with relatives, as adults they understand the importance of visiting themselves. Its in their teen years that people begin to drift apart and people stop visiting.

Bloqs was designed in response to this issue: How can we, assuming no radical change in incarceration trends, help incarcerated fathers reconnect and maintain connections with their children on the outside.

Captivated

The Bloqs project began with the notion of creating a cultural translation for the game Captivated, by the Social Games Against Crime team at South Denmark University.

Captivated is a board game layout out similar to Monopoly which represents a fictional Danish prison. Players progress through the prison, encountering characters who belong to groups or factions. The players learn about the characters and their experiences while also collecting Story, Action and Be Honest cards.

Story cards tell stories about the fictional prison, including interactions between the characters, intended to demystify prison for the child. Action cards ask the player to perform a physical challenge, intended to increase intimacy and bonding through touch. Be Honest cards foster interpersonal communication through the telling of personal stories.

The winner is the first to build up enough currency to buy the prison master.

Prison System Context Differences

Not only is Denmark’s population size far smaller than the UK’s, but their prison population is only 4,000, compared to the UK’s 96,000 at time of research.

Danish prisons are much more standardised than the UK, one prison more or less looks like the next. In addition, the level of amenities is far higher, with a strong bent towards rehabilitation.

When visiting, the visitor and inmate have a private room for periods of a time (typically 1 hour we were told) during which they have a table and other items in complete privacy.

Contrast this to UK meetings which are typically held in one large room on an array of small clusters of table and chairs. Guards line the area and patrol, with a control tower located somewhere. Inmates are only allowed brief moments of physical contact at the beginning and and of the meeting and could have the meeting cut short and be subjected to strip search if they violate this.

Inmates wear high vis vests and must remain seated in a specially designated chair. In one prison we visited tables were simply sawen-off logs with plastic chairs chained to them.

The one exception to this is open days, or family days in which dedicated space is cleared for games, bouncy castles, stalls and such. Families can spend up to eight hours along with inmates and many of the restrictions are removed.

The context of where the game was to be played was the most challenging aspect of the entire project, one which we were not able to resolve in the standard visits. We decided that Bloqs would be constrained to family days and could have applications in therapeutic settings outside of prison.

Blow’s questions were designed to probe areas our research found pertinent to the target users as opposed to Captivated which focused on using the prison itself as the common ground for bonding to occur.

During development, Bloqs was tested with different user groups including younger kids, university faculty, ex-convicts of women’s prison, retirees, and each of our families over the Christmas break.

Serious and Social Games

The term Social games comes from the definitions layout out by Thomas Markussen and Eva Knutz in Playful Participation in Social Games (2017) Download Playful Participation in Social Games here

In short, a serious game is one which is aimed at engaging the player in some form of intellectual engagement and uses the context of game play to facilitate this engagement, where enjoyment is not the motivation for play. An example of this could be a simulator for acting in a profession under a crisis situation like a medic making quick decisions in a war zone.

There also exist Health Games which aim to perform an auto-therapeutic function to a patient, helping them to process an event or ailment.

A social game goes further to extract the primary engagement away from the game and onto the relationship between players. Social games exist to use the game context to facilitate an interaction between players for the purpose of exploring or developing the relationship between them.

Presentation of Bloqs + Site

Bloqs was presented during the Summer 2019 Central Saint Martins Degree Show under the Diploma in Professional Studies section.

In addition to the physical prototype, I designed and launched a promotional site for the project www.bloqs-game.com.

I included some new-at-the time features such as an interactive diagram built with D3.js to explore the SPT. Most of the graphics were taken from or inspired by the instruction set and packaging visual language.

Development

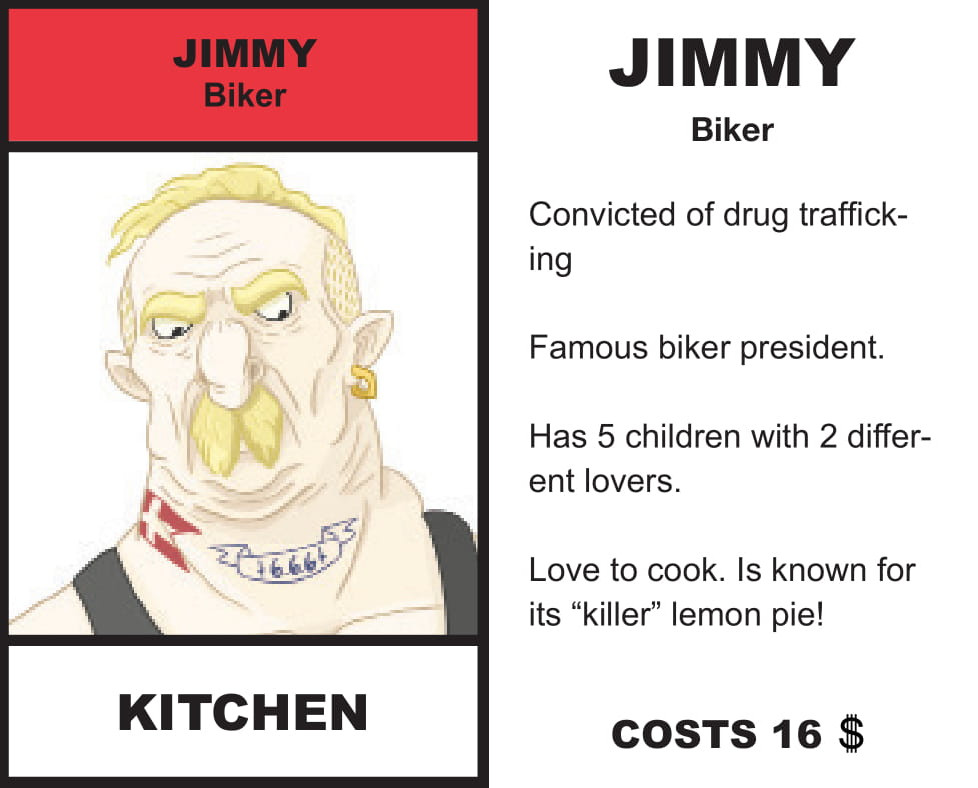

The project began with the intention that Captivated could be directly ported to a UK context so the first three months before Christmas were spent building games around it’s general layout and mechanics.

This involved workshops modelled around the type run by Markussen T and Knutz E, to see if we could build characters which roughly represented sections of the population without stereotyping.

Doubt was present from the start as to whether this technique, which Captivated relied upon was useful from the start. The characters were deliberately cartoonish and exaggerated to add an element of humour. We trusted that the characters were appropriate to a Danish audience but could not distract ourselves from the more problematic elements of the game. For example the gang entitled “The Ghetto” which featured two Muslim men, one of which had 14 children and the other, named Kebab, who’s interests involved Marijuana and Kebabs.

These doubts were compounded when we struggled to get anything close to a taxonomy of inmate to model characters about.

It was already obvious that the UK differs vastly in local culture and idioms, that a joke common in one place may have different connotations in another, that there was a complex interplay of class and deprivation along strong location-based lines. As it turns out, this is reflected in the prison system where it was told to us that often gangs form around postcodes and social hierarchies are complex.

This meant that, even if we could create a set of inmate archetypes that were flexable and relatable as characters, we would struggle to make them relevant beyond one or two prisons. This was the primary reason that Bloqs moved away from the prison context entirely.

The first Bloqs iteration came from a need, while exploring alternate game modes, to rapidly test random prompts in batches, in an organic fashion. The game worked well enough that we showed it off as a side peace during a faculty end-of-year party and it ended up overshadowing the main game. A few more workshops later and it was clear that we had found the new format, the old game was discontinued after the Christmas break.

While running early workshops with both inmates and children, it became quickly clear that the Be Honest cards were the most interesting part of Captivated. The developed the adaptation based on this premise orienting the game play around encountering as many as possible.

Manufacture

During the period where we were still working with a direct adaptation, I came up with the new circular board, designed around advice from a prison commissioner we were in contact with who suggested that a dart-board radius would be most likely to work across multiple prisons. I designed little 3D-printed pieces, modelled off of objects associated with prison.

I also elected to come up with the aesthetic and design of the currency which we named ‘Squids’. The design started almost as a joke, using the image of a squid in place of a dollar or pound sign, however after minor alterations the theme was made subtle enough to add an amusing touch to the design. I endeavoured to make the aesthetic mature and have a realistic touch but still easily identifiable as mock game currency.

Choosing the colour scheme was a long and involved process for the team, we wanted something friendly and calming but not child-like or likely to be perceived as “soft”.

My colleagues took the task of manufacturing the Bloqs, first by laser-engraving the text in a single batch process, then by developing a technique to place multiple Bloqs together, so the outsides could be painted all at once. The last detail was to use a punching set to engrave numbers on the sides, corresponding to the level of the Bloq, so that new players would not need to keep consulting the instructions.

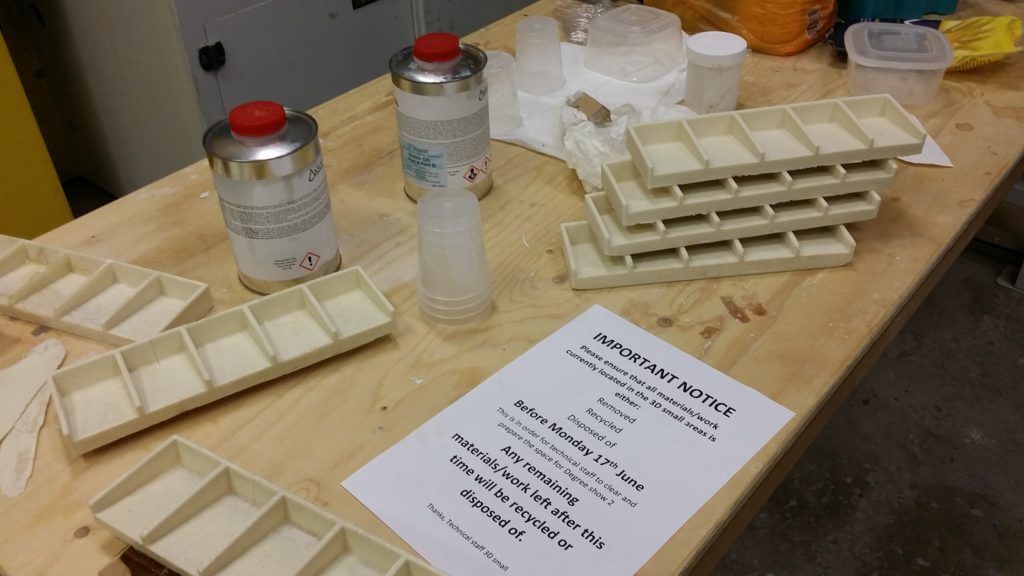

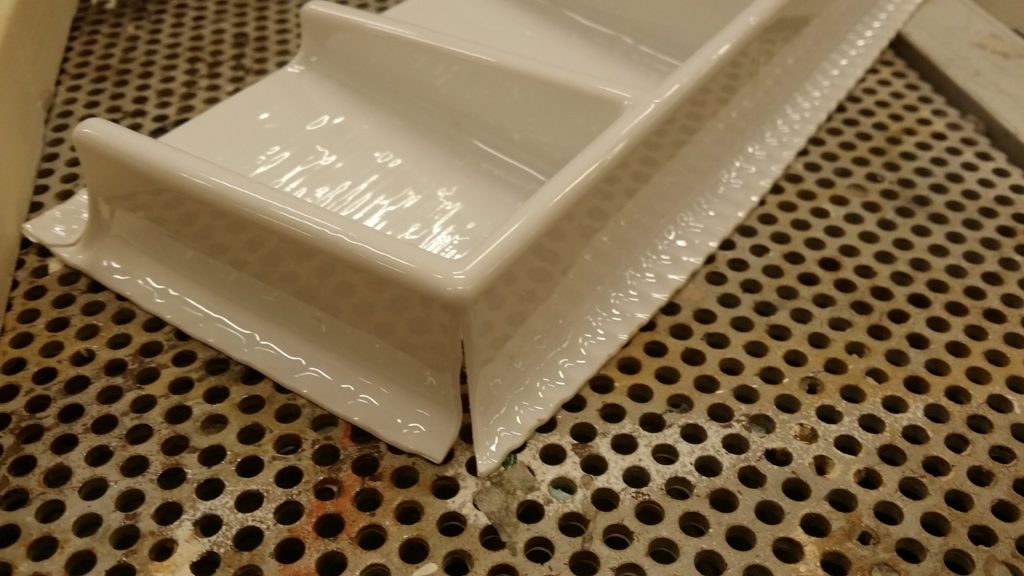

We worked to solve the issue introduced by the currency, that more loose items added opportunities for items to be lost, with little chance to replace them often. To do this, we settled on a currency tray and itirated over a basic design.

I took the design and refined it down to shave precious millimeters off the overall dimensions as space was at a premium. The final design was 3D printed in three parts and glued together. This was then used as the basis of a polyeurathane mould which we would sand down and spray paint.

I attempted to then use one of these to vacuum form an acrylic sheet but the result put too much stress on the edges and corners. The solution would have to involve inflating the shape to increase the radii of all corners which would be infeasible.

Reflections

In retrospect, the decision to drop the old format in favour of Bloqs was an obvious step, in fact, one could argue that it made sense to drop the old game much earlier, that it’s flaws were too obvious.

Yet, it took me a while to get used to it, I was stuck in a mindset of developing the old game and found the change to be abrubt and out-of-tune. Ofcourse in hindsight it was obvious that I was too close to the project, and that a widening of perspective was necessary.

This changed the way I looked at projects going forward, always mindful that metaphorically having my nose to the screen could damage my ability to guide the overall direction of the project. Breaks are good, guys!

Right now, more than ever before, fundamental flaws in our societies and institutions are becoming more obvious, more pronounced, more unavoidable.

You will have noticed that I make no bones about the fact that I was, and am, a staunch prison-abolitionist.

That’s another thing I took from DAC, their no-nonsense mincing of words and stances. We figure that other people, people in positions of influence, are plenty capable of making rationalisations and down playing things on their own. There is therefore no need for you and I to soften our statements. If anything, in making ourselves more bold, more direct, and more unavoidable, we simplify things for everyone.

This was one of the best projects I’ve had the privilege of working on. However, one thing that sticks with me to this day is a subtle yet nagging question which looms over any endeavour like this one.

“Are we just adding a plaster to a gash?”, “Are we providing a method to ignore the root cause of the problem, rather than solving it?”, “Are we facilitating each other in avoiding an uncomfortable reality?”.

Working in prison is surreal, the architecture looks almost like a school, only the fences are two high and the locks too thick. You see reminders constantly that you are surrounded by institutional violence. You forget, when working with the men, who are ostensibly the same as any random person you could encounter on the outside, that they will not get to go home, that most of them are probably still there as I write.

I was surprised one day to see a design from one of my year group come across my twitter feed, in the context of an article about the ‘Safer Cell Furniture’ project, which aimed to reduce the number of self inflicted injuries and suicides by creating safer furniture.

Thank about that for a second. Put aside the actual designs and the real need for more comfortable, more human furniture for a moment.

We have a problem; too many people are going into this system and not coming out, or are coming out traumatised. And our solution is to design furniture that makes it harder to kill yourself? Ok, so we do just this, the statistic “number of dead people” goes down, and… that’s that?

I was impressed by much of the work produced for that project while having the same reservations as described above. That being said I could not disagree with the derisive comments left bellow, much to the tune of the last paragraph.

One comment in particular, jumped out and has haunted me ever since, namely because it put into words something I had been trying to wrap my head round for a long time.

In my experience, the problem with design thinking is that is rewards thorough answers to exciting questions over useful answers to boring questions.

Twitter user @nthnashma 08:14 9/4/20

I soul-searched during this project and long after it ended because of this asking if we were simply creating a new, exiting way to not have to think about the real problem.

In the end, the conclusion I came to is that, our project existed in a very defined scope, we had a unique oportunity and insight to inject something into a pre-existing relation that otherwise would already exist. In other words, it was not possible for this project to ever “fix prison”.

This can become a deriliction of duty, a chance to turn face away from the bigger problem the mement we stop doing work at the boundaries edge. We must view projects like this as one small vector to attack the problem and then go further, ask what other ways we can affect change.

Our intervention is a clean up, and its good at being one, it should never be called a solution, or anything close.

For example, for many in DAC this meant confronting people in positions of authority, making them confront uncomfortable truths, never passing an opportunity to apply pressure.