Have a look at this image of a road near my parent’s house. Pretty ordinary, eh?

In many ways it is. This is the Ayr road, and is a microcosm of the transport and urban design situation in the UK. And I’d like to talk about what insights we can pull from this rather plane road.

This is an arterial road near where I grew up and where my family live in East Renfrewshire, a suburban area about 7 miles out from Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland and the third largest UK city outside of London.

There is currently a consultation to remove the protective bollards on the bike lane which were put in after the Covid-19 pandemic started.

I’d like to air my thoughts and make a case in favour of active travel but I also want to use this as a chance to talk more broadly about active travel.

Who is this post for?

This post is split in two; the first section is the core of the issue and the bit that’s most important while the second, longer section involves a deep dive into the subjects touched on.

There are three types of people I’d like to focus this post on:

- People who drive frequently. Specifically people who don’t really give much thought to bike lanes, active travel and all that stuff. Maybe you get annoyed by cyclists, maybe you have your own local change to parking or street layout that bugs you, maybe you have to commute in traffic every day or maybe none of that is true. For you, I hope to appeal to you without being condescending or patronising, to give you an insight into what people like me are pushing for and to offer a different perspective on roads and driving.

- Local People. Anyone local to the area who are eligible to take part in the consultation or similar consultations near you.

- Interested in Active Travel. People who are already interested in active travel and public transport advocacy, to give you more vocabulary to discuss instances like this and ways to discuss the topic with other.

The Road: A Dramatic and Riveting History

This is the Ayr Road, it was built as a dual carriageway arterial road for Newton Mearns. Later, a modecome of sensibility prevailed and it was reduced from a mini highway to a single lane each way at 40mph (65kph). At some point painted bicycle gutters were added on each side and a reservation island was built in the centre with painted margins on either side.

In 2020, using COVID-19 funding, the road installed some semi-protected bike lanes and reduced speed from 40mph (65kph) to 30mph (50kph). The protection for the bike lanes came in the form of “flexy bollards”; thin plastic bollards spaced apart which have a small hump at the base where they are screwed onto the road. On impact with a vehicle they fold over and sometimes deform or break away, causing at most aesthetic damage to the vehicle.

Flexy bollards are not ideal as they don’t really physically protect people from vehicles but in this case the justification was that they were faster and cheaper to install than permanent bollards or other barrier.

Flex-posts are not a long term solution as they do not offer sufficient protection and deteriorate over time so are often reasonably cited as a scourge of urban design, but they are a quick and cheap way to create a rudimentary physical separation of lanes in a short space of time and I think should not always bee seen as an inherently bad thing. As we’ll look at in later sections, flex-posts are still better than nothing and can literally be installed overnight so are an easier political sell.

The Consultation

East Renfrewshire council has recently proposed ripping out the bollards on the Ayr road and adjoining Fenwick road, and returning it to its previous state; an unprotected bike lane and 40mph (65kph) car traffic.

This is cited as being due to the fact that flex-posts, are not durable and not suitable as a long term solution, and that the COVID relief funds which were used to install them are no longer available for renewal. Rather than upgrade the road to full grade-separation (at reduced long-term maintenance cost it should be added), they would rather just remove it.

East Renfrewshire put out a public consultation asking for opinions on the current plans to remove the bollards and re-increase the speed, presenting a form with pre-made questions and calling for comments.

The posts have now been removed and the road put back to its old dangerous form, with the 5th May local elections coming up some conservative councillors are claiming it was a great victory and reason to be re-elected.

I initially wanted to make this post as a quick call-to-action but while planning it out I changed direction. I believe the decision is not only wrong and short-sighted, but its indicative of a wider problem in UK transport planning about how things like this (and active travel generally) are framed.

However, as I began to lay out my response and expand on some of the points, I found more and more to write about, more examples to use, and more comparisons to draw. The Ayr road is not only a typical example of how poorly Active Travel is implemented but also the barriers to changing the way we think about Active Travel, transport, and urban land use in the UK.

I want to lay out this dynamic as I see it and provide counter examples to demonstrate what change is needed and how that change might realistically come about.

Why is it important to speak up about little things like this?

With situations like this it is really easy to downplay the relative impact of a consultation or a single road project. What difference will it really make? Will the councillors really listen to me, or anyone? What can really come out of a single consultation of a single feature of some road? I don’t even use that road, what does it matter?

So here’s the thing, I’m not here to convince you that the best way to change the world is to engage with consultation forms on a local council websites. This is not a discussion on the merits of engaging with representative democracy.

What I will say is that, regardless of what representation you have; 1) People need to know what you think to know what matters, 2) People in power are still people, you should not make assumptions about what they know and what they don’t know, you cannot guarantee that a concept is something they’re already familiar with.

I think it is important to speak up on topics like this to make clear your ideas of how you want your local environment to be to which ever governmental structures exist, if for no other reason than to override the knee-jerk reactionary comments you expect.

It is important to let your representatives know what you want and expect, even if they’re already onboard they’ll likely base their actions on what they believe there is political consent for.

Lastly, I’ve recently had it demonstrated to me that sharing knowledge on topics like this, even if a lot of it seems obvious or redundant, is worth doing. A story from someone I know rammed this home for me; this person, as much a layperson as I am, had their material used in a course for real traffic engineers. While this might be taken as an indictment of the engineering institution in their country, I think it goes to highlight that as professionals we’re all too often taught to do the job that exists, and not think too much about criticising it. Its good to continually share what you know, even if you think its obvious or that you’re not an authority.

My Response

This consultation asks participants to choose between some multiple choice options and offers the chance to write a response. The following paragraphs are what I submitted, then the rest of the post serves as an explainer delving into the concepts mentioned in my response.

Admittedly my response was quite glib and could have been longer but I deliberately wanted to keep it short and readable for others looking at the comments.

Physical separation of cycle lanes is crucial to increasing safety for all road users and encouraging active travel.

Ideally a grade separated path or curb separation should be used but even a ‘soft’ barrier such as the ‘flexy’ posts currently installed create a visual barrier which encourage drivers to leave sufficient space and not to unconsciously meander into the cycle lane.

In addition, a clear demarcation of cycle and road lanes communicates that cycling (and other light vehicles) are prioritised and seen as a valid mode of travel, it prevents things like pavement parking and blocking of the cycle lane.

Active travel has great benefits including reducing congestion and pollution, reducing road wear, and personal benefits for the individual’s well-being. It also makes it easier for people who cannot drive to get around such as young people, people on mobility scooters, and equipment like velo-mobiles.

As countless examples from European countries show, the only way to induce demand for active travel and the benefits it brings are to provide safe and convenient ways. (add “to do so”, add “to meet Scottish government guild lines)

In an ideal word, the national government would follow the examples of nations like the Netherlands, who saw a relatively recent ‘revolution’ in active travel by redesigning their road building guides to include active travel provisions; every time a road needed resurfacing, active travel lanes would be simply built in at a much lower cost than adaptation (of already existing roads).

While this is outwith the scope of the two roads under consultation here, you already have a “Dutch design” (in the road design as stands); the cycle lanes are comfortably wide, there are relatively wide pavements and plenty of space for cars, and lastly there are single direction paths on both sides of the road (this is far preferable to a single two-way path).

I would implore East Renfrewshire not to undo this achievement and to go further to celebrate it and to push for more upgrades like it.

The more provision there is for active travel, the more appealing and accessible it (the option of active travel) becomes to the wider public, which is what is needed to support gradual modal shift.

To remove the barriers (or fail to eventually upgrade them to a curb) relegate cycling to the domain of people (brave enough to do it) doing it for sport; the relatively fit, usually male, road-bikers.

One thing I’d really like to pull out of this is that, this bike lane is pretty mediocre all things considered.

However, compared to what exists in much of the UK it is in-fact light-years ahead. I’m perhaps a little overeager in my praise of ER council but I do want to highlight that they actually have a pretty good thing going here.

They should not only not rip out the bollards, they should be holding the Ayr road up on a pedestal, saying to other local areas “Hey! look what we can do! Aren’t we forward thinking?”.

The lanes are a decent width, they cover a relatively large area, and connect areas of retail, businesses and residential areas alike, creating a large corridor of transport between urban centres. There are also individual lanes for each direction of travel instead of a bi-directional track.

Bi-directional paths are common in Glasgow where both traffic directions on the same lane. This can work in low traffic areas or in specific scenarios but generally speaking is bad; it reduces space for cyclists, makes overtaking more difficult, and generally goes against how we think of traffic movement. For instance if I want to catch a bus travelling east on an east-west road I expect to go to the north side of the road, having to cross the road to the wrong way just feels odd.

The Ayr / Fenwick road is a fairly big arterial road linking Malletsheugh, Newton Mearns and Mearnskirk with the Avenue shopping centre two high schools, north bound it becomes the Kilmarnock Road and then the Pollokshaws Road strait into the city centre. Prior to the opening of the M77 it was the main road route into the city for a wide area.

A key point

Something I want to point out regarding the consultation and the road is that no space has been taken from the car lanes, the bollards have in fact been placed on the inside of the bike lane.

In the description for the consultation there is a specific reference to parking provision, perhaps a tacit acknowledgement that before the bollards were put in place, parking in the cycle lane was so prevalent it was often unusable.

Parking in the lane still happens, given that drivers can simply enter in the gaps put in for driveways and junctions, but became far less prevalent when the bollards went in. Its now common to see the service and maintenance vehicles that have permission to park, do so on the pavement with deliberate care to leave both the pavement and bike lane clear.

Naturally there will be people responding to the consultation because they want to be able to park on the lane with impunity again, but for the sake of being as good faith as possible I’ll continue this post assuming that this position is a small minority.

Flexi Posts & Road Safety

Painted “bicycle gutters” have a range of problems, roads often deteriorate towards the edges; waste, drain covers and temporary signage are all pushed to edge increasing the risk of being pushed into the kerb and falling.

However, one of the biggest problems with relying on paint is that we as drivers have a tenancy to centre our vehicles in the roadway. Its instinctive; if you are in the middle of the ‘path’ you are treading the most secure and straight route, we do it even while walking on dirt trails. While piloting a 2-tonne metal box at speed, the centre of the lane is intrinsically the safest point, equal distance from obstacles on both sides and spreading the margin for minor errors evenly.

Painted road markings are used as part of that margin of error; they give directions and demarcate boundaries without actually enforcing consequences for minor errors in the same way that a physical barrier would. The typical example are merge markers; they instruct you how and at what angle to merge with another stream of traffic, but if you’re a little bit off you don’t (yet) hit a wall.

Take the example of the reservation islands used on the Ayr Road. The physical island provides a safer* way for pedestrians to get across, crossing one direction of traffic at a time, but also serves as minor physical protection should a car stray off towards the opposite lane should the driver pass out for example. The purpose of the painted margins is to enforce the actual safe distance for the road while providing a margin of error should the car understeer (turn at a larger radius than the road is at).

This might seem like a sensible design but in reality it is a requirement bourne of the fact the road’s design speed and legal speed are too high, the road is badly designed. “Designed speed” refers to the physical speed the road can hypothetically support physical, separate from the enforced legal speed limit.

*Pedestrian islands are another example of this same consequence; if the road layout were changed to be more safe and efficient, the islands would not be necessary.

Some painted lines will “enforce” their boundary more strongly than others; for instance the type which cause tyres to make a noise when run over at speed such as you’ll find on motorways, giving physical feedback to the driver. Others, such as dashed lines, specifically indicate areas where the barrier can be traversed.

In short, painted markings tell you where you are supposed to be but don’t actually keep you from going over.

As established, most people tend to centre themselves between the physical obstacles on either side of themselves while driving, typically the kerb on one side and the the other lane of traffic on the other side, both of which threaten consequences should we stray over. We align ourselves using the nearest physical barriers instinctively before looking at what the road paint has to say and maybe making a conscious correction.

The point of all this is to say that even good drivers who are more than happy to share the road and not to intimidate or assault cyclists will, on occasion, slip further over into the cycle lane than is safe. Providing any barrier, even one which doesn’t physically shield the cyclist, makes drivers take a more central position in their own lane and therefore makes both driving and cycling more safe.

More crucially however, they make the riders feel more safe, which is absolutely crucial to encouraging people to get out of their cars and jump on a bike.

In summary, flex-posts are not a long term solution, they don’t offer proper protection but they are cheep, fast, and economical. If you have a political structure that is reticent to spend money for fear of “waste”, flex-posts can be a way of getting partial protection in place which can be used to justify full protection later.

We should not ever have to choose between 900 meters of partial protection or 200 meters of full protection, we should fund good design as needed. However, too often this is the political choice we have to deal with, and a cheaper quicker option is very often an easier political sell, and an easier way to cover larger distances.

Creating Options for Travel to Accommodate Everyone

There’s a wee bit of a climate emergency on at the moment. Not sure if you’d noticed.

I’m not going to reiterate all of the detrimental effects of cars on the environment because this post would never end because I’m going to assume that its obvious to most that cars are detrimental to the environment.

I do however want to pick up on one thing; there is this idea amongst a large number of people that electric cars are the solution to the environmental effects of cars and solving local transport. According to this mindset, the problem with cars is the exhaust pipe only. Other emissions, infrastructure costs and manufacturing carbon costs are not fully accounted for, and street / urban design doesn’t factor in to most people’s thinking at all.

Electric cars solve only one of the myriad problems of cars; that being the exhaust fumes. Electric cars still produce brake-pad particulates, tire particulates (one of the largest sources of microplastics in the world comes from car tires), and particulate wear from the road surface which they damage as they ride. The amount of lithium mining and other manufacturing necessary to swap all ICE (internal combustion engine) cars for electric is plainly impossible. New electric cars don’t have any carbon benefits until they have completed years of use. And that’s assuming those miles are inevitable; they needed to be travelled in a car in the first place.

Now, despite all this, I am not anti-electric-car. If you have to take a car trip and there are two vehicles to choose from, one electric and one diesel, then the choice is obvious. Of course electric cars are better than ICE cars, if you need to make a car journey and have a choice between an ICE and electric then the choice is clear. However the idea that we can swap out all cars for electric and the world’s problems will be solved is just false. We still need to reduce the number of cars & car journeys.

There are also far more social and economic problems associated with car dependency that don’t go away once you’ve made a perfectly eco-friendly car. Many of us live in car dependant areas where many journeys are not accessible without a car, where the trips and amenities needed to live day to day are only paratactically accessed with a car because they have been spaced apart and there is no other convenient option. Our town centres and high streets are often clogged with traffic and parked cars making them unpleasant places to be. As I experienced going up, kids grow up in environments where they cannot travel far independently, needing to be ferried about in cars, and where even small residential streets are covered in cars.

We need to end car dependency and reduce the number of necessary car trips, not just to reduce emissions but to increase social mobility as well. The best way to do this is to give people choice about how to get around.

If you can go to the shops, the post office, the dry cleaners, the community centre, the school, the park etc. by walking or cycling safely and quickly, quality of life increases. When shopping you can make smaller trips with more frequency as opposed to the ‘big weekly shop’, and you don’t have to worry about getting half way home having forgotten something.

Of course, many people will still want to use a car even if other transport options are viable, this isn’t really about them. Every study on the subject of transport patterns shows that the vast majority of people don’t actually care what transport mode they use, they’ll use the fastest and / or most convenient (or if you like, least inconvenient) so long as it is safe.

As Jason Slaughter of the Not Just Bikes YouTube channel likes to say, there are very few “car people” or “train people”, most just want to get from A to B with as little hassle as possible. I write this as one of the few “train people”; given a choice of a 20 min bus journey and a 40 minute train I’ll choose the train because I like them more, but people like me (who would preference in the same way) are actually statistically quite rare.

The reason that people walk in walkable areas, take the tube in London, cycle in Amsterdam, and drive in Huston is because these are the most convenient modes respectively for each city. Often times “culture” is cited as the reason people choose particular modes, and while there is an element of getting people used to new ways of doing things, culture is still the result of behaviours, what people actually do, and is not set in stone changing with relatively little effort.

By giving people choice and by making the options safe and convenient, people will use it, even some don’t want to, and if that option is the most convenient then the numbers using it will only increase.

We owe it to ourselves and future generations to create provisions that enable active travel and make it a viable option, campaign after campaign “encouraging” people to “try active travel” will not succeed if these options are still not seen as safe or convenient.

The Rest of The Post

So that’s the end of “part 1”, the main post. What follows is a deep dive into specific design features and a comparison to other case studies.

The rest of the post is over 18,000 words long, if that does not appeal then you might want to stop here.

If you’re up for a deep dive and have a fresh hot drink prepared, then lets continue on…

What we can learn from the Netherlands

I was recently introduced to the YouTube channel Not Just Bikes. Run by Jason Slaughter, it documents his family’s experience moving to the Netherlands, his observations about life there vs his home town of London Canada, and discusses various aspects of active travel and car dependency.

It is difficult to really define exactly what his channel is, but I like to think about it as a 101 on Dutch design, how the Netherlands built their “active travel utopia” through a push for safer streets, and how their towns looked like any other European city until the 70’s when grass-roots activism laid the groundwork for what exists today.

In the 1990’s in the Netherlands, the great cycling capital of the world, the best you could hope for was a painted bike lane. There were efforts from some politicians fighting to remove bike lanes from congested areas as late as the 90’s.

Just like almost every other country in post-war Europe, the Netherlands had its own plans for an auto-driven recovery, for massive highway projects to plunge through their city centres, and the same earnest attitude that “if everyone can drive, why would anybody do anything else?”. Just like the UK in this era, cycling was widespread, and just like the UK, its prevalence was seen as a problem yet to be solved.

There was an explicit political motivation to get rid of the bikes, cyclists were descried in such terms as “locusts”, an “infestation”, a remnant of the old, and that they needed to “get out of the way, and make way for the motorcar!”. Bikes were the primitive past, and motorcars were the bold modern future that needed to be unstuck.

Just like the UK, there were extensive protests against the massive road-building projects and a move for safer streets to protect children. The only real difference is that their movement was more successful than the ones in the UK. The oil crisis of the 70’s is often cited as the reason why; that the UK’s response was to upscale drilling in the North Sea while the Dutch felt the pressure more which aided the safe streets movement. However, it is difficult to really know what caused the outcomes to be so different.

Today it is possible to go most places on a bike in the Netherlands, travelling on safe, grade separated cycleways and dedicated routes. Bikes are seen as a legitimate mode of transport and almost always outnumber cars.

Almost all roads and streets have protected bike paths, with the remnants of the 90s painted bike lanes being steadily upgraded. Many of their city streets are completely car free, their traffic lights dynamically react to bikes, trams and cars to turn green on approach and prioritise certain modes of travel.

Modal filters are used to create ‘desired routes’ for different modes of travel; cars take the long route round in many cases and avoid urban centres, while other modes can go straight through. Trams travel different routes to the Metros making sure to cross them frequently while buses are routed to avoid conflicting with trams. The Dutch have a word for this that roughly relates to “the untangling”; the principle is that if you try to maximise throughput for every transport mode in every area nothing will move, it will all conflict.

If your a frequent driver you’re probably thinking “that sounds hellish, imagine all the traffic”. Yet the opposite is true.

Because there are safe accessible routes and a range of travel options, the only people who drive are those who need to or want to. If you love your car and love driving everywhere, you still can! But most likely you wont want to. If you need to bring a car or van into an area that de-prioritises cars you still can, just don’t expect to go as fast as the main car routes. As Jason puts it in one of his videos:

“I think, I’ve started to appreciate, one of the really the really toxic things that comes out of car dependent places is that everyone is forced to drive, and they think that this is providing them with this comfort and convenience but driving sucks in car dependant places. There is so much traffic, there’s people cutting you off, there’s people that obviously don’t want to be there, they’re board, they’re looking at their phone…”

“…I mean when you take everybody and force them to do something whether they want to or not, it sucks. And you get all of the road rage and you get the terrible driving and this is where it comes from, but you have to do it, to even feed yourself, to go to a job, literally anything you have to go through this highly undesirable experience.”

Jason Slaughter (2021) Not Just Bikes with Jason Slaughter. 30 November. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQSp7T5CaPo (Accessed: 21/04/2021).

On being a driver in the Netherlands he says:

“One of the things that surprised me about the Netherlands is its awesome to drive here like, I cannot explain how great it is to drive a car in the Netherlands. I actually drive a lot, there’s various time when I need to drive… there’s so little traffic, the traffic lights work so well, the big thing that makes it so great to drive here is that, the only people who are driving, are those people who want to drive or those people that need to drive and that’s it.”

Jason Slaughter (2021) Not Just Bikes with Jason Slaughter. 30 November. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQSp7T5CaPo (Accessed: 21/04/2021).

Bikes as Transport

Very often, those of us invested in public transport and sustainable transport talk about cycling and active travel as a ‘side-effect’. We focus on the trains, the trams and the trolley buses. We talk about the hierarchy of inter-city travel to suburban routes, metro systems and buses, and then make offhand reference to “yeah and I guess there would be more active travel and bikes n’ stuff, something to do with the 15 minute city” without any specific idea of what this will look like.

This attitude focuses on the commute and fails to describe what local urban design should look like beyond “train good car bad”. It unwittingly downplays the local, day to day, and littler journeys that make up a great deal of our lives, and we forget about the benefits of existing in a space and enabling community growth.

We assume that reducing congestion, eliminating car journeys, and having spaces for people to live in just sort of happens once you have enough trains and trams.

The Netherlands presents a more defined vision of how localities can be transformed. In the late 20th century, there was an activist movement which was only really focused on the goal of making streets safer, the cycling was an unanticipated result that came along with pursuing this goal.

They had their own road building projects, their own plans to plough highways through their major cities in the name of “modernisation”, their own vision of a suburban, car driven future. The safe streets movement faced fierce resistance and won its victories later rather than earlier. Everything we now associate with the Netherlands, particularly the cycling culture, was an unexpected side effect of a movement focused around making streets safer.

The Dutch design codes used to guide construction and renovation of streets was redesigned largely based on the Crow Manual. Any given street needs to be repaved and rebuilt every 15-30 years depending on the road due to wear and tear, by incorporating active travel designs into the guidelines for doing so means the infrastructure comes at little cost.

Retrofitting a road to have a dedicated bike path has a cost associated which can often put authorities off the idea of proposed single projects to do so. By changing the design codes to have bike paths, accessible pavements (side walks), and traffic calming measures built in, you get them almost for free. The features are simply a part of the road’s specification, if you’re going to have to replace the kerb anyway, it costs next to nothing to simply move it over a bit.

Of course cost is not an excuse for not retrofitting an existing road even if you must do it on a project by project basis. However by simply incorporating the feature into the design guidelines, you build consistency and widespread connectivity faster than a case-by-case basis. You build up the expertise in the organisations and labour forces that are going to do it anyway, rather than brining in costly consultants to do one ‘project’ and then leave.

Its worth pointing out that this does not just apply to dense, inner city and urban areas, these designs permeate out to suburban and rural areas as well. Your typical single-family, detached, suburban housing still exists in the Netherlands if you want it. The difference is that in the Netherlands your kids can travel to the park themselves safely, they can cycle themselves to school without fear they’ll get mowed down by an SUV, they can (parental permission willing) visit shops, takeaway restaurants, go to the cinema, and take part in extra-curricular activities, all without being tied to their parent’s car and schedule. They need not wait until they are old enough to get a driver’s licence to have lives of their own.

Up until the late 20th century, much of the Netherlands looked remarkably similar to the UK. A quick internet search will bring up numerous ‘before and after’ pictures of car-clogged streets with architectural styles similar to many high-streets in the UK, transformed into spaces which not only accommodate everyone but are cleaner, nicer places to be.

The image bellow is from an article on sustainableamsterdam.com and shows the street of Maasstraat as it looked in 1977 and 2014. This is actually a outdated design given that there are only painted bike lanes and not protected bike paths.

Doesn’t this look rather… ordinary? Mundane? Easy?

Sometimes we, as sustainable transport advocates, fall into the trap of defeatism while discussing the ongoing urban design trends of the past 50 years or so. It is admittedly difficult to look at the endless new developments of environmentally damaging, car dependant sprawl built with giant car parks, next to enormous motorways, and not feel a bit daunted. Compounding this is the fact this type of development seems to be the only major house-building happening in most of the country.

When you begin to see through the inefficiencies in existing street design, and when you become familiar with better designed spaces, you begin to see how even the worst of car dependent suburban sprawl can be drastically improved without even initially taking space way from cars (although you should totally do that too). After all, Amsterdam wasn’t built in a day.

One of the things that stands out about Not Just Bikes is the mundaneness of the things Jason talks about. Part of this is deliberate, Jason talks several times about the fact he makes his videos specifically un-cinematic to avoid a sense of drama and to point out how ordinary these “revolutionary” features can be. He also talks about how a proportion of his audience is Dutch and watches his content because they are interested to find things they take for granted are not normal elsewhere. They get to see their lives and their ‘normal’ from an external perspective, and learn that it hasn’t always been this way.

Visions of the Future from the Past

The concept of almost everyone owning a car and driving everywhere is an experiment.

It is an idea from a post-war world searching for a path to recovery, borne of a need for fresh thinking and new ideas, and cemented in the 60’s and 70’s.

It is difficult at time to imagine that the attitudes and political zeitgeists of a time so close as the 1970’s was so different to ours, after all most of us would consider those decades to be roughly the beginning of the modern eara, post WW2.

Another commentator whom I have great respect for, railway Permanent Way (track design) engineer and writer Gareth Dennis points out, when we consider things like the Ringway projects of London or Dr Beaching of the infamous report The Reshaping of British Railways we must remember that attitudes and understandings about the car were fundamentally different.

Michael Dnes. London’s lost ringways (2022) Available at: http://transpressnz.blogspot.com/2010/11/days-of-future-passed.html (Accessed 11/06/2022)

Dr Beaching, for example, is blamed for the majority of massive railway cuts that took place in the 1960’s, and is often portrayed as a car-obsessed, railway-hating fanatic, slashing at the network with gleeful abandon. In reality he was just a man, commissioned to produce a report on the current state of the railways, which was then acted upon by superiors that did not have sufficient foresight to see that what they were doing was wrong. They were not innocent, but they were also not ideologically driven, moustache twirling villains (those would come later).

People in that area found themselves looking at graphs showing rail in terminal decline (to rebound unexpectedly in the 70’s), massively rising car ownership and improving bus ridership, and made decisions based on the attitudes of the time. For instance, there was a strong belief that people would switch between modes with frequency, driving to stations and parkways to ride trains into metro areas, that buses would replace small infrequent trains as they were more versatile.

We now have information to know better, it seems obvious that such lines of thinking were flawed, and yet in this time they had no precedent to draw on, they had to come up with a new image of the future. This is not to make excuses for the mistakes of the past but to recontextualise the thinking that gave us our current status quo.

There was a time when developing suburbs where everyone could have their own detached home with a little garden and drive everywhere was not only a practical response to housing shortages, but was also sold as the height of aspiration. When you look at much of the imagery from that eara, their vision of the future was Jetsons-esq, with everyone flying along in their own individual little pods between large towers. The motorway wasn’t a necessary evil, it was new and exciting! The future was little pods, liberating everyone with their convenience.

Old image from an advert above by America’s Electric Light and Power Companies from the mid-1950s. Available at: http://transpressnz.blogspot.com/2010/11/days-of-future-passed.html

The issue was that the world they built served little pods, and only little pods. Public transport waned, the suburbs sprawled out, previously favoured urban centres entered decline in favour of spread-out box stores and shopping centres. Every street was converted to modern standards to try desperately to speed up the motorcar which just kept getting stuck in traffic, while more and more public space was given over to them to try and alleviate congestion; for much of the population car dependency was born.

Car dependency (not cars in general) is just another idea of a future, one that we tried, and one that hasn’t panned out.

We can keep our cars, you can personally keep driving everywhere if you like! But its time our streets were designed a bit more sensibly to accommodate all users, and to not force people to drive who can’t or just don’t want to.

It is time that we re-thought the function of streets and roads, realising that the “street” is a destination first and a thoroughfare second, while “roads” are high speed corridors between spaces. It is time that we stopped perusing the smooth flow of just one type of vehicle at the expense of all others. It is time we evaluated whether we all really do just love our cars that much, or if in fact what we actually love is the freedom they afford us. It is time we ponder if and how that freedom could be achieved in other ways.

And most of all it is time we stopped pandering to prevailing myths about car dependency, traffic, and congestion.

Making a commitment to accommodating active travel involves a need to look beyond short-termism, old conceptions of congestion relief, and the convenience of being able to park in an unprotected bike lane whenever you like. It will take time to develop a critical mass of adequate infrastructure and encourage modal shift, it is not a quick fix but an ongoing and active effort to value personal mobility beyond the car.

Even well designed streets are the result of a process of continual review and redesign which is ongoing. By the time the UK looks anything like the Netherlands does today, the Netherlands will surely look vastly different. This is not about swapping out one fixation with another, it is about adopting an attitude of enlightened design.

Urban fabrics have never been static and are always engaged in a cycle of re-use and repurposing depending on the demands of the day. The urban fabric we’re used to in the UK is not the way it has always been and is certainly not immutable, it is time to re-examine how we allocate space and ask what values we would like to embed with this era.

Some Important Points to Keep in Mind

Intended Speed vs The Design Speed

There’s an old concept in road design that wider lane width and lack of obstacles is directly tied to increased safety; that it gives drivers a greater margin of error for minor mistakes and reduces the chance of a head on collision.

This idea is based in sound logic; you need some margin of error to be able to make small mistakes without crashing, the punishment for a slight twitch on the wheel should not be injury or death. However, after a certain point increasing this margin of error the effect on safety begins to move in the opposite direction.

Separating oncoming lanes does reduce the chance of collisions if the vehicles are already travelling at high speeds, you’d certainly never build a motorway without physical barriers between traffic directions. However at lower speeds it encourages drivers to drive faster because they feel safer going faster.

The same goes for other obstacles; if the road is grade separated and designed for high speeds then yes, having a line of trees at the side could be disastrous, but for anything at lower speeds you are likely to simply make drivers feel safer and driver faster. The more clearance and error margin you give drivers the more comfortable they will be driving at higher and higher speeds, at a certain point this begins to eat any safety gains you got by clearing the route in the first place.

The speed at which an average of motorists would potentially feel safe driving at is referred to as the design speed of the road. There’s no specific formula to determine the design speed but there are various ways designers estimate it.

One way you can think about design speed is to imagine a world in which speed limits didn’t exist, in which we were all urged to use personal responsibility to judge the risks for ourselves much like the UK government’s current Covid-19 policy. In such a world, what speed would people drive at on a particular stretch of road? What feels safe? What could you get away with if it was quiet? How do you estimate others would act? This is the design speed.

Modern traffic engineering should in principle consider the design speed of the road as well as the intended speed, and should add or remove obstacles based on this. One of the most prevalent mistakes in UK road design was, and still is, to take actions which increase the design speed of the road in the name of safety and assume the posted speed limit will be enough to enforce safe speeds.

“Many of my engineering colleagues will reply that they do not control the speed at which people drive – that travel speed is ultimately an enforcement issue. Such an assertion should be professional malpractice. It selectively denies both what engineers know and how they act on that knowledge.

For example professional engineers understand how to design for high speeds. When building a high speed roadway, the engineer will design wider lanes, more sweeping curves, wider recovery areas, and broader clear zones than they will on lower speed roadways. There is a clear design objective – high speed – and a professional understanding of how to achieve it safely.

There is rarely the acknowledgment of the opposite capability however; that slow traffic speeds can be obtained by narrowing lanes, creating tighter curves, and reducing or eliminating clear zones. High speeds are a design issue, but low speeds are an enforcement issue. That is incoherent, but it is consistent with an underlying set of values that prefer higher speeds.”

Charles L. Marohn Jr (2021) Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pg 6

An example of the detriments of a high design speed is the Barrhead Road, a typical main road with a posted speed of 30mph (48kph). It features a range of features which increase its deign speed above this, all of which have been or will be discussed in this post, namely the use of pedestrian barriers to compensate for pavements that are too small, large turn outs for turning lanes, wide clear zones, and lack of obstacles. All of which come together to increase the design speed to something way above 30mph.

In early 2021 a car travelling in excess of 100mph (160kph) sped westbound down the hill and almost made it around the corner before mounting the clear zone near Balgray Road, and launching itself into a house on the corner (number 1 Balgray Road). The car smashed through the bottom of the house destroying most of the ground floor. Luckily no one except the driver was injured, everyone inside was apparently upstairs sleeping at the time. The house was almost condemned but was able to be repaired and is now up for sale.

A road like this should be designed in accordance to this speed. It should never have been physically possible for someone to reach 100mph and turn their car into a torpedo. And yet, after such a dramatic incident, absolutely no action was taken to prevent something like this happening again.

In countries like the Netherlands, after every major crash or fatality occurs, a comprehensive design review is performed to ascertain why and how the crash happened. It is acknowledged that safety is influenced by the physical design of the road, and often redesigns are performed to prevent the specific incident happening again. This rarely happens in the UK, traffic crashes are attributed to the personal behaviour, and personal responsibility alone.

Its actually a pretty mediocre bike lane.

OK look, I know I’ve been signing the praises of this bike lane on the Ayr Road, and there are things ER council genuinely got right.

However, in may respects it only warrants such praise because the bar is so incredibly low to begin with. Rolling it back would be bad but that does not mean it is in any way perfect.

If I’ve got you to read this far, I assume the argument in favour of providing proper infrastructure for multiple modes of travel and good street design benefiting everyone has been illustrated, even if you find you still disagree on the points. By talking about problems this case study still has and by looking at more examples I can hopefully get you to build on this idea and begin to re-imagine how streets could be redesigned, how space could be optimised differently, with relatively little effort.

So lets talk a bit about what they got wrong.

Bike Lane width

If you use something like Google Map’s time travel tool you’ll see that the bike lane used to be smaller than it is now but even at its current width it’s not really big enough. In addition, the posts have been bolted on the inside of the painted line reducing its with further, perhaps because they can’t be secured on the paint itself.

The base of the bollards isn’t that big, maybe about 40cm across, but this can make a difference when the total lane width is only about 1 meter to begin with. In addition, the height of the bollards mean that you can’t swerve as close to them as you could with smaller ones given that the profile of a bike and rider is top-heavy.

Having wide bike lanes isn’t just about the ability to overtake, if the lanes are wider there is a dramatic improvement for safety for cyclists and boosts confidence because there is more space between you and the cars, all for the sake of about 50cm or so.

Central reservation and gutter

Almost the entire length of the Ayr road includes a central reservation created with a kerb area for physical separation, and a painted hatched area to enforce a recommended safe distance.

The presumed reasoning for this is that the physical kerb protects the minimum safe distance between lanes and will protect the driver should they accidentality veer over, while the hatched area represents the optimal safe distance plus a margin of error. In addition, the central refuge provides pedestrians with a “safer” way to get across, although I personally do not feel particularly at ease standing on a plinth between two lanes of 40mph / 65kph (or faster) traffic because the road is too wide to traverse all at once.

This design was implemented when the road was reduced from four lanes to two and presumably seemed the safest option given the speed limit remained at 40mph (65kph). However the result is a road with a design speed far in excess of 40mph. This can be evidenced by the fact that many people could be found travel along it quite happily at 50mph (80kph) and even now, few people stay at or bellow 30mph.

If this were to be redesigned properly, the two lanes should be pushed closer together, eliminating the hatched area entirely and perhaps removing the central reservation entirely. This is not about making the road ‘less safe’ for the intended limit, but about making it less safe to exceed said limit, there is no reason to be travelling at motorway speeds on a supposedly residential street.

Of course by eliminating or at least reducing unused space in the middle of the road you then have ample space to put in a proper bike path, better bus stops, and maybe even some parking.

In fact, Fenwick Road, which the Ayr Road turns into, demonstrates this. Despite having many of the same problems as Ayr, Fenwick road has a minimal central reservation and wider bike lanes.

I would argue that this is still very far from being safe but serves as a great demonstration of how much space the Ayr road is wasting and how much could be reclaimed without affecting throughput at all.

Bike lane crosses turning lanes

At intersections the bollards have been placed in such a way as to preserve as wide a turn out as possible. That means that the rider is exposed to potential turning vehicles for longer and have to contend with cars turning as faster speeds.

At the junction next to Whitecraigs station a left turn lane forms out of the parking lane, separated by a side road turn out. The bike lane continues straight ahead into the cycle box. This means that traffic turning left has to merge across the cycle lane.

Presumably the designers of this layout believed it was better to keep the bike lane moving straight, allowing cyclists to maintain their speed and not have to turn. Perhaps they patted themselves on the back for their ingenuity getting a turning lane ‘for free’.

Incredibly dangerous, turning lanes that cross bike lanes create a concentrated conflict point between cyclists and cars meaning both parties have to anticipate the other’s movements to prevent side-swiping. In addition, it makes cyclists pull up between two lines of cars which is uncomfortable and risky.

These types of merges are prevalent in the US and are the bane of bike infrastructure advocates, it would have been better to merge the bike lane left into the space left by the parking lane, and putting the turning lane on the right.

There’s a gap on Fenwick Road

This is less a criticism of the project itself, which as I understand was never going beyond the finish point on Fenwick road, but a criticism of a lack of joined up thinking more generally speaking between Glasgow authorities.

When the large bike lane on Fenwick Road reaches a junction with Church Road it stops and turns into a ‘sometimes bus lane sometimes parking lane’.

It stops completely later on and isn’t present through much of Giffnock, despite the area being a more residential and commercial area and containing a school.

This whole area is a bit of a mess. Even driving through it is uncomfortable and confusing. The road fluctuates between being a four lane road, to sometimes three, swapping sides frequently, sometimes it has parking and sometimes not, at some points there are as many as five turning lanes and parking.

Finally, at the Giffnock Police station, the bike lane reappears. In total this gap is only about 500 meters but the area is congested and messy enough that it doesn’t matter.

Having to navigate a number of large difficult junctions and areas lined with pedestrian fences is enough to definitely put you off before you reach the measly bike lane at the other side. This bike lane, despite offering little, carries on until it reaches the edge of Shawlands.

If this area, which involves a density of housing, shops, restaurants and a school, would be made safer and more pleasant, then it could create a path directly from the Shawlands area all the way to Newton Mearns. It feels like an oversight that for the sake of 500 meters this utility has been missed out on.

The junctions and roundabouts are still really bad.

The Eastwood Toll is a large two-lane roundabout connecting the Ary Road and the Fenwick Road. Measuring about 65 meters across, its four adjoining roads have curved entrances and exists and all connect with two lanes in either direction. If there was a specification for a “high speed roundabout” this would qualify.

Naturally, there is no cycling provision but to add insult to injury, the bike lane does not even formally end as it approaches the roundabout, the paint just kind of.. stops.

On one section of pavement approaching northbound there is a blue “shared path” sign, implying there is some idea that bikes should mount the pavement when the lane ends and use that to navigate round. However, aside from this sign there is nothing else to indicate this is what you are supposed to do, its possible the blue sign is just there for bikes exiting Eastwood Park.

Here is where the bike lane ends as it approaches from the south. Note the care homes on the left and the fact the lane shrinks to be too small to fit even the cycle stencil inside of the lines.

And here is how the bike lane ends on the southbound, about 200 meters travel distance from the roundabout. Is the intention that cyclists should turn into the pavement here?

If you do, you’ll head down a pavement and straight into people exiting a barber shop, you can then cross the four lanes of the Eastwoodmains Road, navigate through some winding streets, until you reach the top of this overgrown staircase in the second image, about 180 meters from where that bike lane actually starts.

If this is indeed the intention of the route planner then I would suggest it is a bad one.

Pedestrian Barriers are Not For Pedestrian Safety

Sometimes called ‘guard rails’ or just ‘fences’, pedestrian barriers are ubiquitous in the UK. Most people assume their purpose is to protect pedestrians from collisions in areas where they cannot easily be avoided.

What most people don’t realise is that these barriers crumple like wet paper on impact, they provide minimal impact resistance. An observably large number of stretches of these fences have dents or other minor damage which some might assume is from signifiant crashes, however most of these dents come from low velocity impacts or large vehicles simply backing up too far and not noticing they had even made contact.

Compare this design to the crash barriers used on motorways and other vulnerable areas; those barriers are much lower to the ground because a crashing vehicle is best stopped by controlling the centre of momentum closer to the wheelbase. They are continuos corrugated strips attached to the ground by poles on the opposite side of the impact area, this means that on impact kinetic energy from the vehicle is redirected horizontally and spread along the direction of travel, decreasing the chance of the vehicle overpowering the barrier.

This is a clever and cost effective design, and very different from the spinally, hollow tubes found on pedestrian fences, loosely connected to each other and the ground with often just a single bolt.

The design and ergonomics minded among us will also note another subtle aspect of these fences; they’re not tall enough to fully protect pedestrians if, for instance, shrapnel from a crash comes over or a wide vehicle gets too close to the edge. However, they are tall enough that even a tall adult will struggle to climb over in a hurry. This is compounded by the vertical struts which stop you being able to get a purchase and are placed close enough together that you cant fit a foot between them.

The reason for these features is simple; the main function of pedestrian barriers are to prevent pedestrians from crossing at certain points where they would impede cars, straying too close to the edge in areas where the speed is too high, or leaving the pavement where it is too small.

This is useful in allot of places, for example when you have a path connect to a road on an incline, it stops any loose prams or people running from accidentality running straight onto the road. However in the majority of use-cases they are used on corners and high-streets where the pavements are too small and there is a ‘risk’ pedestrians will try to use the space allotted for cars. When you have squeezed as much road space as possible to try and make cars go faster and have none left for people, those people get penned into ‘their’ space.

These barriers are traffic control for people and compensate for bad design, there are very few instances where they are actually necessary because of some geographical feature or other.

Pedestrian barriers are not to protect you from cars. They are for protecting cars from you.

Haggerty, G. (2018) Damaged Pedestrian Barrier after Van Crash. Available at: https://www.grimsbytelegraph.co.uk/news/van-crashes-through-pedestrian-crossing-1213818 (Accessed: 24/03/2022)

Pedestrian Cages Reduce Travel Convenience for All

An extension of the idea that pedestrian barriers are for the benefit of drivers and not for pedestrians; very wide / fast roads, badly designed junctions, and other features designed to try and squeeze as much capacity and speed from cars as possible, bring with them a feature that I like to call Pedestrian Cages.

Sometimes called ‘staging areas’ or ‘refuges’, these are areas in the middle of the road that split a crossing in two with two stages. Often the two sets of lights and crossing points are separated to avoid people trying to go straight over. These are typically surrounded on all sides with pedestrian barriers and almost always require you to wait for quite some time while traffic whizzes by.

I like to call them ‘cages’ as you feel penned in, the second priority, sitting tight in your special box to give the important traffic maximum time to pass.

Pedestrian cages often require users to move in strange ways because the entrances are not in the same position or becuase they are built on some other strange set of road geometry to, and they are frequently chained together meaning you have to cross multiple times. While these crossings make attempts at being physically accessible, the need to stop and turn frequently and to stand and wait in small areas decreases their accessibility overall.

People do not behave like vehicles; the more difficult it is to cross the street, the more likely people simply wont, decreasing the amount of people choosing to simply exist in an area. From a commercial standpoint, street spaces with amenities on both sides decrease the number of spontaneous consumer interactions lowers due to the effort to cross over.

Cars need a lot of infrastructure to work and staged crossings / cages are part of that, they are features that increase the amount of equipment needed for an area with minimal to no proportionate benefit, all for the sake of a bit more speed or a bit higher capacity. This can result in large areas covered in asphalt, fences, poles and lights which is not only not aesthetically pleasing but are environmentally damaging as well.

There are also cases where pedestrian cages are used to justify a more hostile street design, people walking are forced to use them with the effect of actually slowing down traffic due to the lights being used to cross so often; if people could cross more easily traffic would not have to be stopped so frequently.

While writing this post I came across the bellow tweet purely by chance, but I think it’s really illustrative of what a lot of our urban areas in the UK look like. John asks “Where am I?”, a difficult question to answer, as they really could be anywhere.

In pursuit of speed, every other requirement this junction might have is compromised, including capacity. In Confessions of a Recovering Engineer, Charles Marohn explains that engineers’ obsession with speed is a holdover from the early days of traffic engineering, a field which is young enough some of it’s early practitioners are still alive.

He explains how at the turn of the 20th century there was already a strong road network, mostly made of gravel or dirt tracks, sometimes paved to no particular standard. One of the fist things traffic engineers did following the brief to increase automotive mobility, was to pave the roads, make them uniform, and remove obstacles creating speed gains which were directly correlated to mobility gains. In other words, they figured out that speed = mobility = efficiency and that value has been embedded into the practice since.

If you ask most people which they would choose in a trade off between speed and capacity for a given road, almost all will say capacity. After all, what’s the point of taking 30 seconds off of the travel time only to get stuck in traffic? Yet the embedded value placed on speed results in messy, inefficient layouts like this which only deliver benefit at non-peak times and make everything else worse for everyone.

Roads, Streets and Str-odes

Marohn and the Strong Towns foundation define a Road as being a high speed connection between two places, its primary purpose to be the movement of people with few entrances and exists. A motorway is the ultimate expression of a road. A Street is defined as being a space for communities to build wealth, unlike roads, streets are destinations first and de-prioritise throughput, having slower speeds, lower car capacities. Streets are spaces for people to be and exist, cars and other motor vehicles are guests.

A Strode is a street-road hybrid which purports to give the speed and capacity benefits of a road, with ll the community wealth benefits and amenities of a street, but in trying to do so fails at achieving either.

Strodes are mini highways that plunge through communities, they are dangerous; being often built like motorways they allow individuals to reach alarming speeds when clear, but most of the time they are also completely congested creating wall-to-wall gridlock. Strodes are hostile to people outside of cars but they are also pretty unpleasant for people inside cars too. Strodes are a failure of separating concerns, to the detriment of all of their users.

Here is example of a particularly nasty strode in Darnley, an area that is residential but has pushed aside most other things to make way for big box stores and car infrastructure. It is covered in asphalt, pedestrian fences, and lights yet still does not deliver signifiant speed or capacity.

I recently found myself on it while attempting to cycle to the Silverburn shopping centre. Having to walk my bike along the pavement, the yellow line indicates the route I had to take, the red blobs are where I had to wait, each wait being out of sync meaning 2 minutes at each.

At one section I had to cross to a mini island and wait for another set of lights to change as the turning lane had been given priority separately from the forward lane, another capacity increase effort.

I appreciate the image quality is not great but you can view this link instead and imagine trying to, for example, visit the local shops from the housing estate.

This whole effort could have been avoided with the use of simpler crossings further away from the junction, however the design ethos of the road was to minimise the amount of time each lane had to be stopped, meaning pedestrians are forced to move in keeping with the cycle of the cars. More individual crossings for pedestrians means fewer lanes for cars blocked at any one time, the pedestrian’s journey can be cut up to give more priority to cars.

This type of infrastructure pretends to cater for pedestrians but in actuality treats the existence of them like a pest, by only allowing you to cross when it can be absolutely assured no cars can be given priority instead.

The Other Case Study

If all this has you thinking “even when we do get it right in this country, we still get it wrong” then let me offer a look at what things could be, with proper planning and proper design.

Shawlands is another sort-of-suburban area closer to the city, it has a mixture of low and medium density housing and connects to the Ayr / Fenwick road as the Kilmarnock road.

Shawlands is a different area than Newton Mearns but is quite similar in terms of street design, setbacks, and layout, featuring a similar mix of housing types and density.

As a demonstrator of this mix, the first image bellow is Glasserton Road, a low density street, lined with detached and semi-detached houses with big gardens. The second is Clarkston Road near to Cathcart station, a mixed use development with amenities and flats and, according to Google, is a 7 minute walk away from the first image. If you are unfamiliar with UK cities this type of mixed zoning pattern is pretty common.

For extra context, here are two streets, each about a 10 minute walk from the Ayr Road in Newton Mearns. The first two images are of the same position on Kings Drive looking both north and south, the second is Broomburn Drive, which is the next street over.

This is obviously different to Shawlands, but the point is to illustrate that Newton Mearns has even more space and wider, more flexible roads, so therefore has even less of an excuse for making bikes and cars alike struggle for space.

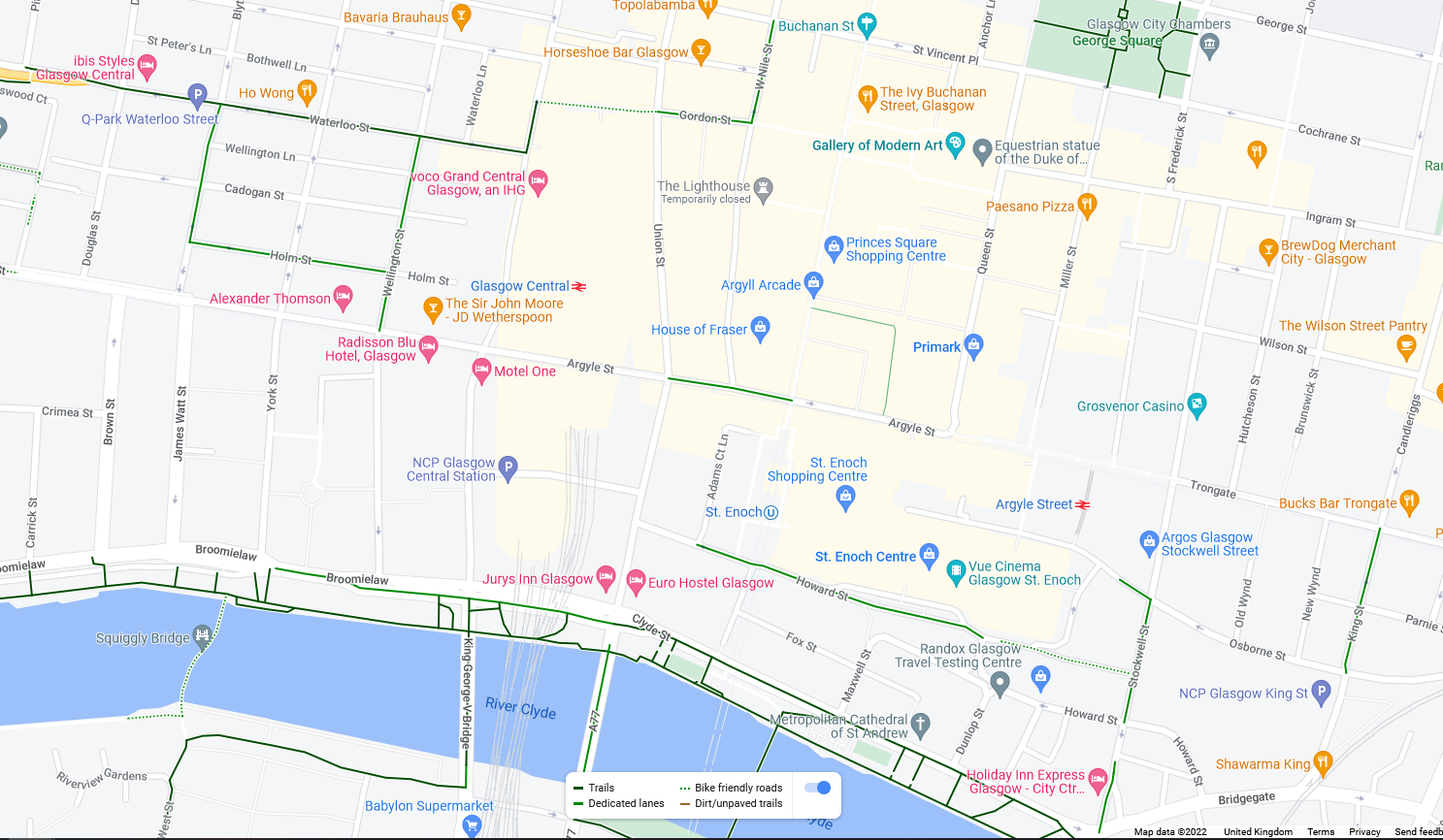

Our case study is the Victoria Road, a dense single-file road which leads from Victoria Park into the city via the Victoria Bridge (but also connects to the Crown Street Bridge).

While this is a very different type of road given the surrounding environment and traffic expectations, it has the same theoretical capacity as the Ayr / Kilmarnock Road; one lane in each direction and turning lanes. It has bus stops which inline with the lane and it has high quality bike lanes on either side for each direction of travel.

As the Ayr Road turns into Fenwick Road which turns into the Kilmarnock Road, it then turns into the Pollokshaws Road. The Pollokshaws road is a 6 minute walk from the beginning of Victoria road at the point of the image above, the two converge at Eglinton Toll and diverge again into the city.

It is home to the South City Way project, a fully grade separated bike path that follows some design decisions so good its almost Dutch. It’s certainly better than a lot of the “Cycle Super Highways”; the mediocre bike lanes which London calls acceptable.

How it Used to Look

This is a view of Victoria Road in 2015 looking south towards the park, about 100 meters down the road from the position in the above image, where Albert Avenue joins it on the left.

Note the range of bad design features:

- Pedestrian barricades to restrict crossing points.

- Pedestrian cages with two sets of lights making crossing the road an effort.

- Road is too wide and fast to safely cross without using the lights increasing pedestrian journey times and increasing the number of times drivers will be stopped at the lights.

- Wasted gutter space in the middle is necessary to maintain the design speed but serves no one.

- Zig-zag lines are necessary to slow and re-centre vehicles as the approach the crossing which takes up space that could be used for parking and other uses.

Throughout this article I have put a driver-centric point of view in many of my arguments, this is a deliberate attempt to really drive home how good street design benefits everyone, including drivers, and to try and pre-empt some expected objections.

Notice how this road layout impedes almost everyone, including motorists with the lack of parking provision, all to make way for through speeds that are as possible.

This is a street, like so many others, that has been pushed aside to make way for people in cars to pass through with as little inconvenience as possible. When streets are designed around throughput they are effectively saying “this destination is not as important as peoples’ ability to pass it by”. This is not a place to go, it is a place to get around.

Here is the same street location looking both north and south from 2020.

A marked improvement in so many ways for all users, including drivers.

I said before that what’s really interesting about this project is how simple the adaptations were, and yet how transformative the effect is.

Victoria Road in 2015 looks just like so many other roads in the UK and especially around Glasgow, its not particularly special apart from the connection to Victoria park at one end. It provides a concrete example of what this kind of adaptation could look like while (at least for the time being) maintaining the current level of car through-put and parking, if not increasing it.

Lets look at what these features are and how they work.

What the Victoria Road Gets Right

Continuos Protected Bike Path

The first and most obvious thing is the continuos protected bike path running on both sides of the road. Unlike the Ayr road, these are physically separated by a kerb meaning that unless a car drives directly at them or is going at speed, it will not be able to mount and veer into the bike lane.

The bike lane is not as wide as the modern standard but is still more than enough to be comfortable riding in, and more importantly, it is consistent and changes with gradually at points where it needs to.

The surface is smooth asphalt instead of slabs and there is clear delamination between the bike path and the pavement.

Grade Separated at Pavement Level

Bike paths at pavement level are far superior to those at road level, they are easier to get on and off and they wear better because the entire path is raised instead of a free standing kerb.

This is another thing that the Cycle Super Highways get wrong; some, particularly the older ones, still fundamentally think of a bike as a small, slightly vulnerable cars instead of something between a car and a pedestrian.

As a result they opt to put the bike lane at road level with a kerb between the road and the bike lane which introduces a number of issues but primarily they minimise the ability for users to get in and out and means that any break in the kerb exposes the lane to the road.

They almost get the idea right; that bikes need protecting from cars, but they still have the bikes at road level and frequently expose them to car infrastructure features.

Large Pavements Preserved

Its uncommon but not unheard of for cycle projects to take space from the pavements to supply extra infrastructure like bike paths (because re-designing the car space is clearly unthinkable).

For the most part the pavements are wide enough to get two wheelchairs past side by side and never too narrow to get at least one through. There’s even enough space for some alfresco dining although I’m not sure what the permit situation for that is at the moment.

Good Use of protective ‘Islands’ and Push-Outs

A continuation of the topic of grade separation is that the Victoria Road employs excellent use of “Islands” or “kerb Push Outs” (I’m sure they have a proper name but I don’t know what it is).

These are the bits where the pavement sticks out for bus stops and pedestrian crossings, allowing the bike lane to pass through. This is another thing that London’s Cycle Super Highways get wrong a lot.

The islands give pedestrians a way to safely cross the bike lane with ease, to focus on the car lanes, and get them as close as possible to their destination (the bus stop of the other side of the road) before crossing meaning they can take more time or even cross without having to use the cross button, thus actually speeding up traffic.

The Islands are wide and well maintained, at bus stops they raise up to meet the bus to decrease the step (I don’t know if they are fully step free), and they’re long enough that people can move organically and spread out. The design isn’t just big enough for whatever feature it supports, it acknowledges that people will naturally try and take a direct path to where they need to be and will not necessarily follow the determined route.

As an example of push-outs being used incorrectly, take this junction near Aldgate East station on CS2 in London. This is somewhere I used to cross a lot as a pedestrian to get to bus stop H on Commercial Road.

Its not entirely clear to some people where they are supposed to stand while waiting. Pedestrians are supposed to stand back where the bin and tree in this image are, yet many will want to stand between the bike path and road given the roads massive size and limited viability.

This results in some awkward movements and milling about as some try to stand in the unprotected middle section, some try to squeeze onto the square island with the button, many stand in the bike lane itself.

All of this awkwardness is the result of the fact the kerb edge is too small and the bike lane is not at the same grade as the pavement. The kerb starts and stops and often isn’t big enough to stand on yet sometimes you’ll find yourself on it none the less. From my many commutes late at night crossing here, trying to be mindful of where I should and should not stand, while also trying to get as close to the road as possible so as not to be caught out by the short crossing times, the most generous I can describe this areas is “confused and confusing”.

Then there is this bike turning lane for cyclists turning left. You can see what they were going for with the turning lane and “beg button”, but these are poor compensation attempts for the fact that this road and junction are just too big, to messy and haven’t actually been redesigned at all.

Where are you supposed to go once you turn right on your special bike turning lane? There certainly isn’t another bike path to catch you at the other side. The road designers don’t really know either.

Desire Paths & The Expectation that Pedestrians Act Like Cars

You’ll have seen ‘desire paths’ before, these are where an intended route has been built but requires people to move in a way that is not intuitive, takes longer, or assumes the wrong destination, and so the people using it tread out a new route that is more natural.

Very often this involves the assumption that pedestrians will act like cars and follow a dedicated path, even if it involves an indirect detour, for the sake of avoiding conflicting traffic flows. An example of this is suburban feeder streets which often deliberately wind around and have awkward entrances to side streets; a more direct route is possible but it’s not detriment to cars to go 500m or so further. This is done to make through running (or “rat running”) inconvenient.

Where pedestrians and bikes are concerned this is an inconvenience because a loner distance to walk is just more energy expended. Bike and pedestrian traffic can flow in and out, merging and weaving in very complex patterns, they do not need to be flow controlled nearly as much as cars.

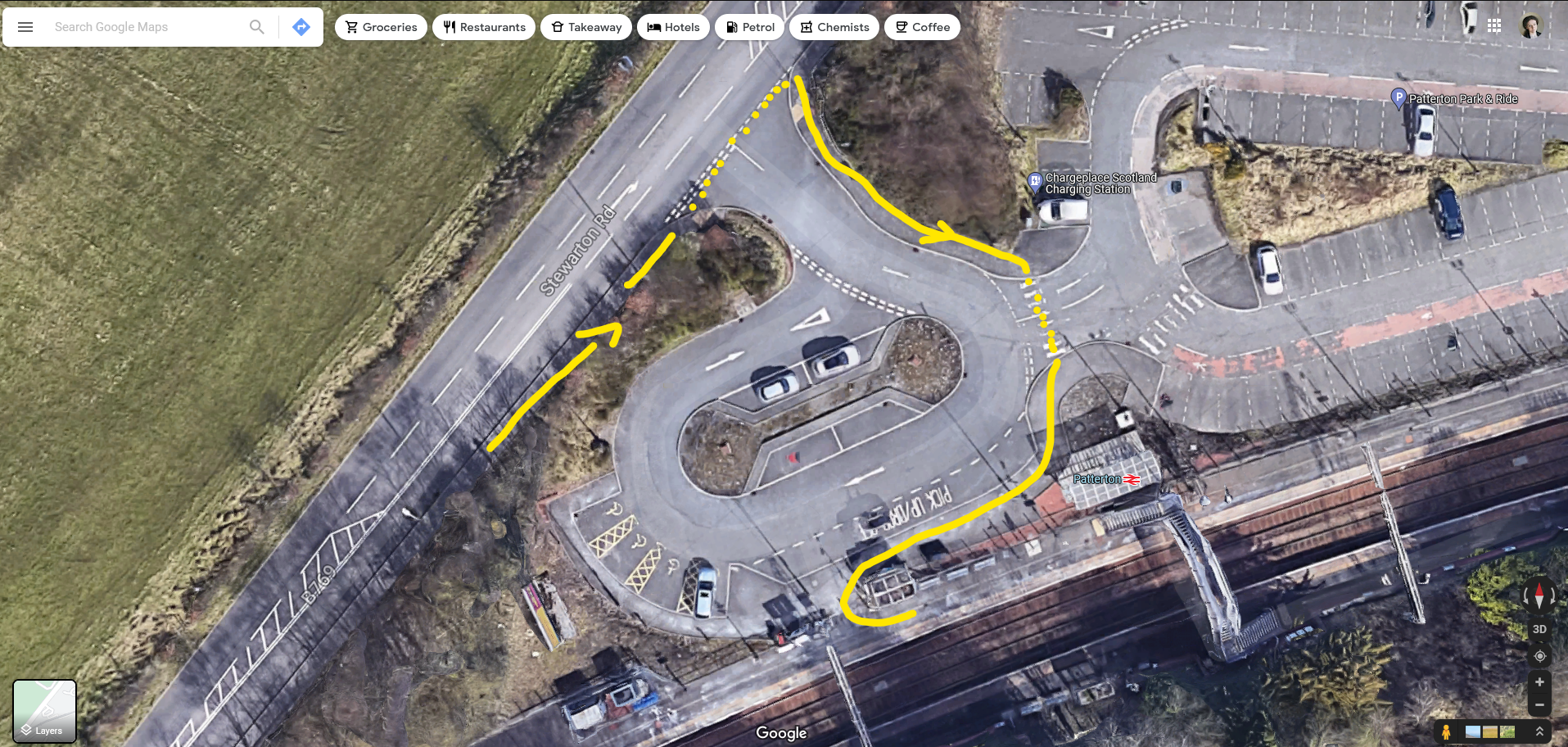

Here is an example of bad pedestrian deign and desire paths from near my parents at Patterton station. Note the desire path on the side of the entrance where pedestrians have walked over the grassy verge. Most of the foot traffic approaches the station travelling north-east and yet there is no pavement on that side entering the station.

The majority of foot traffic is expected to pass the station crossing the entrance, turn round, skim the long way round the drop off zone, and then walk back along to the platform entrance. The route is indicated by the first image bellow by the yellow line. This is extra insulting if you would then have to walk along the platform length again to get to the overpass to reach the other platform.

The second image in that set shows the actual route the vast majority of the traffic takes, walking on a small dirt ledge, through the cars, over this middle reservation thing, and into the station.

Its so accepted that the design is bad that almost all the drivers anticipate pedestrians and will stop and watch out for you. I would love to talk to the designers who implemented this in about 2009, did they really expect this not to happen? Did they really expect pedestrian traffic to happily act like vehicles and take the long route round?

Perhaps they thought there would be so much traffic moving round the drop-off zone that pedestrians had to be kept away from that area, in which case why make them cross over the entrance?

On Victoria Road it is incredibly pleasing to see the push outs offering buffer space, multiple zebra crossings with the accessible texturing, often joined with other features. This enables foot traffic to move dynamically, entering and exiting from a range of directions and rarely having to travel unnecessary distances. This reflects the varied ways in which people actually move and reduces potential conflict points.

For example, the second and third images here show a bus stop which turns into a street crossing and an entrance to a traffic-calmed side street. There are bike racks, bike-share racks and alfresco-dining coffee shops on the corner .

The Eglinton Toll

Further up the Victoria Road it meets the Pollokshaws road before they both diverge into the city centre. This area is a great example of how push outs with multiple entrance / exits aids people crossing the street. Its worth remembering that the Pollokshaws is still a single lane in either direction, despite being an ‘A’ road (larger class road compared to Victoria). At this point it also has two lanes which are ‘sort of bus, sometimes turning, sometimes parking’-lanes.

Both of these screenshots were taken at almost the same place approaching the point they meet, you can just about see the entrance to the petrol station on both. The Pollokshaws does have crossing lights just behind the camera (the images from that position were too dark) and an abundance of pedestrian fences, pedestrian cages and ultra-wide turn outs. Both of the roads are approximately the same “wall-to-wall” width relative to the pavement size.

Now, considering these roads have almost the same through-put, which of these looks easier to cross for someone walking / wheeling a bit slower? Which looks easier to speed a car on? Which road better uses the space available? Which one even looks nicer (accounting for the dull day in the second image)?